Two very wonderful people showed up the other day and presented me with an article from the

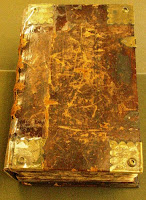

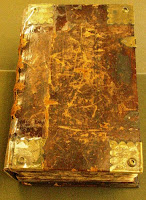

Grand Rapids Press dated June 10, 1967. According the the article, 40 years ago their mother had donated a 1637 Dutch Staten Bible to Hekman Library. The reporter noted that the Bible had been "desecrated by a sword thrust that nearly destroyed it. The marks of the sword . . . are still visible." The article further speculated that "some soldier surprised the congregation and tried to destroy the Bible." Let your imagination run with that for awhile. (Take a look at the photo on the left.) I'm skeptical about the scenario; I'm not so sure that soldiers were busting heads or spearing Bibles at 17th-century Dutch Reformed church services (16th century - maybe!).

But I did find the Bible and we looked at it together for awhile. Family members had written genealogical information in the front leaves. We've kept it safe these 40 years and will continue to keep it in our Rare Book Room. Maybe their children will come back to take a look again in forty years. It's a large format folio 1637 Dutch Staten Bible. This translation became the standard Bible of the Dutch Reformed Church, corresponding to the "King James Bible" (1611) of English-speaking people, and Luther's translation in Germany. Actually we have four 1637 first editions, as well as numerous later editions. One of my favorites is an 18th-century version with a Dutch East India Company binding (you might say this is an early example of what today we call a "

niche Bible" [see also Daniel Radosh, "

The Good Book Business,"

New Yorker (18 December 2006)].

In 1618 at the Dutch Reformed

Synod of Dordrecht, one of the first orders of business concerned a new Dutch-language translation of the Bible from the original languages. Six Dutch theologians were appointed to the translation team: three for the Old Testament,

Jan Bogerman (1576-1637),

Willem Baudartius (1565-1640), and Gerson Bucer (c.1565-1631); and three for the New Testament, Jacob Roland (1562-1632),

Festus Hommius (1576-1642), and

Anthony Walaeus (1573-1639). The translation also includes the Apocryphal Books. While the first edition of the Bible has a printer's date of 1636, printing actually was completed the following year, and the first copy presented to the Dutch Estates General (which sponsored the publication) on September 17, 1637.

The Staten Bible also has extensive annotations and cross-references. (See the photo of Psalm 100 on the right.) The Synod of Dordt gave the translators a number of guidelines. They were to give brief and clear content summaries for each book and chapter. They were also to add brief marginal explanations if the Greek or Hebrew could not be translated entirely "literally." Unclear passages were to be explained briefly. The annotations are important for the history of interpretation, and have influenced generations of Bible readers in the Dutch Reformed tradition. This was the primary Dutch Bible translation until 1951, and has had considerable

linguistic influence on the Dutch language. There is an

online Dutch version which includes the annotations as well as information about the translators and other aspects of the Dutch Bible.

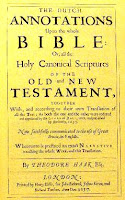

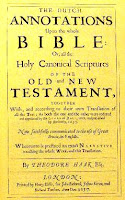

For those who do not read Dutch, an English translation exists. In 1645 the

Westminster Assembly persuaded Theodore Haak (1605-1690) to begin work on an English translation of the Staten Bible. Haak's translation (he didn't include the cross-references or the Apocrypha) was finally issued in 1657, with the title:

The Dutch Annotations Upon the whole Bible . . . A facsimile edition was published in 2002 by the Gereformeerde Bijbelstichting (ISBN 90-72186-31-1 , HL RareBk BS195 .H25 1657a). For those with access to Early English Books Online (EEBO), here's a

durable URL link to Haak's translation.

Those who really enjoy relaxing with a book while surrounded by books will want to order one of these (price: 2250 euros). If you prefer to do most of your reading in bed or at a desk, but like the idea, maybe your dog or cat would like a "cave." That's now also a possibility. Ms. Adachi has come out with a model designed for small dogs and cats. To order, visit her web site: Sakurah.net.

Those who really enjoy relaxing with a book while surrounded by books will want to order one of these (price: 2250 euros). If you prefer to do most of your reading in bed or at a desk, but like the idea, maybe your dog or cat would like a "cave." That's now also a possibility. Ms. Adachi has come out with a model designed for small dogs and cats. To order, visit her web site: Sakurah.net.